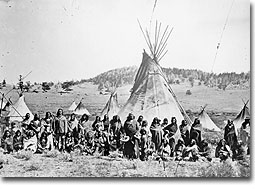

When members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (which church is often misnamed the “Mormon Church”) first arrived in the Utah territory, there were three major groups of Native Americans: the Shoshone, the Utes, and the Southern Paiute. The Utes and the Shoshones had long since acquired the horse from the Spaniards and were able to hunt. The Paiute tribes mostly gathered food and tried to grow what they could in the harsh environment.

Feelings among all the tribes were mixed upon the arrival of the Mormons. Some wanted war, but the stronger influence was for peace. The Saints even settled in what was considered unclaimed land between the tribes, thus for some time none of the tribes felt at all encroached upon. Rather they looked to the newcomers with natural curiosity and the hope of gifts. Soon all trade with the tribes went through an agent in a designated area outside of the pioneer camp. Just three years after the Saints’ arrival an ordinance passed which prohibited the sale of arms, ammunition, and alcohol to any Native Americans in the vicinity of a pioneer settlement. One of the chiefs, who had sought war with the Saints upon their arrival, now saw the wisdom of peace. He strongly encouraged the Saints to settle among his people. This happened much faster and over a much larger area than he had anticipated, however, and things began to grow uneasy. After two skirmishes, a deeper understanding was reached between pioneers and tribes.

Feelings among all the tribes were mixed upon the arrival of the Mormons. Some wanted war, but the stronger influence was for peace. The Saints even settled in what was considered unclaimed land between the tribes, thus for some time none of the tribes felt at all encroached upon. Rather they looked to the newcomers with natural curiosity and the hope of gifts. Soon all trade with the tribes went through an agent in a designated area outside of the pioneer camp. Just three years after the Saints’ arrival an ordinance passed which prohibited the sale of arms, ammunition, and alcohol to any Native Americans in the vicinity of a pioneer settlement. One of the chiefs, who had sought war with the Saints upon their arrival, now saw the wisdom of peace. He strongly encouraged the Saints to settle among his people. This happened much faster and over a much larger area than he had anticipated, however, and things began to grow uneasy. After two skirmishes, a deeper understanding was reached between pioneers and tribes.

As governor, Brigham Young was also appointed Superintendent of Indian Affairs, and he strived to maintain good relations between both the government and pioneers and the Native Americans. The view the Mormons took of the Native Americans—that they are the remnants of a larger civilization, descendants of the tribes of Israel who came to the Americas in 600 B.C. who are spoken of in the Book of Mormon—made the Mormons take a very different approach in their relations with the Native Americans than any other Americans had heretofore taken. They felt a deep responsibility to aid and teach these people and to raise them from their fallen state.

Brigham Young said, “Let the poor Indians be taught the acts of civilization and to draw their sustenance from ample and sure resources of mother earth, and to follow the peaceful avocations of the tillers of the soil, raising grain and stock for subsistence instead of pursuing the uncertain chances of war and game for a livelihood. I have often said and I say it now let them be surrounded by a peaceful and a humane and a benevolent policy. Thus will they be redeemed from their low estate and advanced in the scale of civilized and intellectual existence.”

Ten years after the Bear River Massacre of 1863, in which more than 300 Shoshone men, women, and children were killed by U.S. troops, a Shoshone elder had a dream. Chief Sagwitch, a survivor of the 1863 massacre, and other tribal elders felt the dream was inspired and was instructing the tribe to join The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. After discussing the matter in great detail, the went looking for a Latter-day Saint (“Mormon”) man whom they trusted, George Washington Hill, who lived in Ogden, Utah.

After obtaining permission from Church president Brigham Young, Hill travelled to the tribal lands and performed 102 baptisms and confirmations that day. Over the next four years, nearly 1,200 more people were baptized from the Shoshone tribe as well as other tribes in the Intermountain West. Most of these people eventually settled in Washakie in Box Elder County, Utah, and learned to cultivate the land and become independent. The U.S. government tried to force the Native Americans to move to the reservation in Fort Hall, but Brigham Young refused to let them be booted. Many of their descendant are still in the area. Many descendants express gratitude to their ancestors for converting and learning these techniques, claiming that their culuture was preserved and their freedoms protected by not being forced onto a reservation.

This policy of teaching individuals and communities to learn to support themselves is a core principle of the Church and led later to the foundation of the welfare program that still exists today and led to an improvement of relations between the two civilizations. As a specific example, in 1938, Church leaders requested deer hunters to save their deer hides and donate them to an all-Shoshone branch, to give them more of a livelihood making clothing to use and sell. Brigham Young also urged patience with Native Americans caught stealing or borrowing things, for often there was a large distinction between the two cultural understandings of the principles.

Another struggle in understanding between Native Americans and early Latter-day Saints (“Mormons”) arose in the form of slavery. The Spaniards had introduced the idea to the Native Americans, and the Utes and Shoshone had preyed upon the weaker Paiute tribes, kidnapping women and children and selling them into slavery in Mexico. Slavery in any form is abhorrent to the teachings of the gospel of Jesus Christ, and tensions arose when the Mormons would not buy slaves and also when they looked down upon the practice wholly. The feelings of the Saints produced quite a surprising effect: they voted to legalize the slavery of Native Americans in Utah. Their purpose in doing this, however, was to save as many lives from servitude as was possible. There were strict conditions in buying a slave: the buyer was required to clothe, feed, educate, and ultimately free their charges. While intentions were good on the side of the Mormons, however, their very actions of purchasing the slaves gave rise to the more powerful tribes capturing and trying to sell them more. This sometimes led to gruesome consequences. On one occasion, a chief’s brother, Arapeen, took a captive boy and dashed his head against the ground, killing him, when some of the Saints refused to buy him. Arapeen blamed them entirely, asserting that if they had bought the boy, he would still be alive.

In 1854, Brigham Young stopped on a tour of the southern settlements in Utah to visit with some chiefs who were meeting about tense issues between the Americans and themselves. By this time, most of the Native Americans in the region had begun to make a definite distinction between Americans and Mormons, because their treatment of the Native Americans was so different. One of the main chiefs spoke strongly for peace. Brigham Young urged peace also, and spoke on the behalf of the Native Americans to the government. The government finally agreed to buy all the lands the Native Americans were then occupying in return for the tribes moving to reservations. The government agreed to pay them a certain amount of money each year over the next sixty years and to provide them with public schools. After much deliberation and counsel with Brigham Young on the matter, all the chiefs but one signed the agreement. Tragically, the government never came through on any of its promises. Understandably, the Native Americans fought back, and the pioneers (which included far more Americans than just the Mormons by this time) were forced to fight back. Not only had the government fallen through on all its promises; it also refused to aid those who had to protect themselves against the justifiably furious Native Americans.

The sad history between the United States and the Native Americans does not end there, but the influence and intimate relations the Mormons had with them did. Though relations differed among the Mormons and different tribes, the Mormons tried to aid those whom they esteemed as brothers and sisters of the same God; they tried to teach them and to be at peace with them.

Watch a video about the restoration of the gospel on lds.org

Watch a video about the restoration of the gospel on lds.org