Beginnings of the Conflict

The commandment to gather to Missouri had been given to the members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1833, but Joseph Smith and other Church leaders were still centered in Ohio, so the gathering of the Saints was not fixed on Missouri. On April 26, 1838, Joseph Smith received a revelation from the Lord instructing him to have the Saints build up the city of Far West, Missouri. By this time, most of the Saints had been forced to leave Jackson County, and so many of them travelled west. The Lord instructed that the Saints build up Far West and prepare to build another house unto the Lord. Soon, the Mormons were arriving in droves.

In a matter of eight months, the Mormon population in northwestern Missouri had grown from between three and four thousand to more than nine thousand, with thousands more expected to come. Though initial relations between the Mormons and the Missourians had been peaceful, several factors soon led to tension. The numbers in which the Saints were gathering was overwhelming the citizens of Missouri, and, due to false rumors about the Mormons, many people did not want to live in the same communities as they did. Property values plummeted and ill feelings began to spread.

In a matter of eight months, the Mormon population in northwestern Missouri had grown from between three and four thousand to more than nine thousand, with thousands more expected to come. Though initial relations between the Mormons and the Missourians had been peaceful, several factors soon led to tension. The numbers in which the Saints were gathering was overwhelming the citizens of Missouri, and, due to false rumors about the Mormons, many people did not want to live in the same communities as they did. Property values plummeted and ill feelings began to spread.

The attitudes of some of the Mormons certainly didn’t help matters. It had been revealed to Joseph Smith that the area the Saint now occupied contained the original location of the Garden of Eden as well as the area Adam and Eve had lived in after being expelled from the Garden. The Mormons believed all of this to be sacred ground. The Lord had given them a commandment to build up His kingdom and had promised the Saints the land would be theirs. Some of the Saints unfortunately took this to mean they had rights to all of the land there, and, though they were willing to pay for it, their attitudes affected their neighbors.

At this time, Missouri was very much on the frontier of the United States. There were fortunes to be made by some, and politics played an important role in the relations between the two parties. Though Mormons were free to vote however they chose, and were more than willing to vote for any candidates who were friendly towards them, they did tend to vote similarly. Missourians felt the Saints would soon take over everything by sheer number and that they would soon control the government, though the Mormons had no inclination to do this at all. They simply wanted to live peaceably and build up the kingdom as they had been commanded to do.

Mormons Not Allowed to Vote in Gallatin

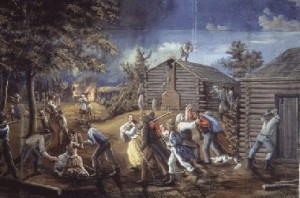

On August 6, the day of state and county elections in Gallatin, Missouri, tensions reached a boiling point. When a group of Mormon men went to vote, they were blocked by an angry group of men. A local judge named William P. Penniston led the mob and, after shouting various insults at the group of Mormons who had come into the town to vote, said, “I headed a mob to drive you out of Clay county, and would not prevent your being mobbed now.” The Mormons, who were few in number anyway, were outnumbered about ten to one. Dick Weldon, who was drunk at the time, insulted and assaulted a Mormon shoemaker named Samuel Brown. Fists began to fly. Though no guns were used and no one was killed, many were hurt. The Mormons came out victors, but were still surrounded by angry Missourians, and the Mormons left without voting.

Joseph Smith was in a neighboring county at the time, and when he heard of the actions the next day, several men gathered to ride over and find out what had happened. Joseph said, “From the best information, about one hundred and fifty Missourians warred against from six to twelve of our brethren, who fought like lions. Several Missourians had their skulls cracked. Blessed be the memory of those few brethren who contended so strenuously for their constitutional rights and religious freedom, against such an overwhelming force of desperadoes!”

Because tensions were still so high, a group of Mormons visited Judge Adam Black, who was reportedly heading mobs trying to expel the Mormons, requesting he sign a document stating he would have no relations with the anti-Mormon mobs. He believed his word should be enough guarantee, but Joseph wanted something concrete to show the Saints to try and ease their fears. Though he was not forced to sign the document, Black felt he was being bullied by the group (mostly of Danites—see below), he feared for his family, and so he created his own document, which he signed. The Mormons were satisfied and let him alone. Black and others soon brought charges against Mormon leaders for their conduct, but the trials seemed only to resolve in building tensions higher on both sides.

Things continued in a cyclical pattern for some time. False charges were raised against the Mormon leaders to try and get them out of the state. The Mormons appealed to all levels of government for help. They wanted matters peacefully settled, but when no help was offered, they felt compelled to form militia to protect themselves. The conflict spread to other counties and soon required the attention of the governor. Governor Lilburn W. Boggs was known to be anti-Mormon and was inclined to believe the worst reports he heard of the group. He organized a large militia to march and went himself to help sort the matter out.

Previous to the governor’s arrival, two generals, David R. Atchison, and Alexander W. Doniphan, arrived with their men and began to use diplomacy and appease both groups. The generals discovered the claims against the Mormons were false and that the Mormons were acting defensively. They sent word to Gov. Boggs that they had sorted matters out, but that if he would still come and speak to the people, they believed that would be of much more use than the presence of the militia. However, when Boggs arrived and discovered most of the trouble to be coming from the non-Mormons, and received the report too late that his gathered army was no longer needed, he returned home without speaking to the people.

Siege of DeWitt

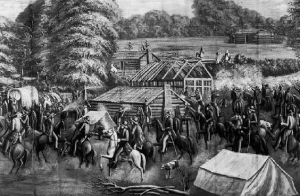

When matters continued uneasily, non-Mormons concluded they would have no peace unless the Mormons left. After telling the Mormons they would leave, however, and even selling some of their land to them, the Missourians resolved once and for all to drive them out of Carroll County. In October, a two-week siege began on the town of DeWitt, and forces gathered on both sides. When the Saints sent A. C. Caldwell, a non-Mormon, to once again petition Boggs for aid, Caldwell returned saying Boggs had refused and said it was a waste of government time and money and that the people would have to work it out on their own. Boggs later denied this, but with both sides believing this to be his stance, the Mormons had no choice but to surrender. The terms agreed on were that the Missourians would pay the assessed value of the Mormons’ property and compensate them, but all the Mormons would have to leave the county. The Mormons were forced to leave, but were only partially compensated, if at all.

No sooner had the Saints gathered for protection in Daviess and Caldwell Counties, than the mobs which had just driven them out of their homes conspired to drive them out of the neighboring counties. The mobs desired the Mormons to leave so they could take their land and sell it to other U.S. citizens coming west.

This victory on the side of the Missourians sparked action throughout the other counties inhabited by Mormons. Each county was desirous to expel the Mormons, and they believed that if they acted quickly, they would succeed. Joseph Smith determined they would fight and took charge of the Mormon troops himself. The Mormons organized militias for defense (which was a common practice at the time—most cities had militias), but a certain segment of the militia, calling themselves Danites, began to be more active in their defense.

It is difficult to say under what orders, if any, some of the troops began raiding and plundering their local non-Mormon neighbors. They seemed to think they were justified in taking the equivalent of what had been taken from them previously. Their tempers finally exploded, after years of persecution and frustration that they continued to receive no governmental aid. Many Mormons began to view all Missourians as their enemies, even though many citizens had helped them in the past. When Missourians retaliated in full force, the Mormons prayed for the state militia to arrive, which it never did. After hearing that vigilantes in Carroll County intended to drive out the Saints, General Parks organized the Ray militia and went to intervene. Upon his arrival, he found true civil war had broken out. Parks wrote to General Atchison asking for help and advice. He was afraid his men would join the vigilantes if he joined the fray, resulting in more destruction of the Mormons. He felt the best choice he could make at that time was passivity. Other generals refused to call upon troops, still feeling that the Mormons were being treated abominably.

Mob Rule and the Danites

In addition to all these stresses, the actions of the Danites, who took it upon themselves to purge and cleanse the Church of the unfaithful, heightened uneasiness.

Due to dissenters in the early stages of the Church, certain members felt the need to purge the Church of the unfaithful and to renew commitments to live the gospel fully. In the past, dissenters had played large roles in stirring up anti-Mormon feelings, resulting in the Saints being driven from their homes. Desirous to avoid being persecuted and driven even more, there was a somewhat antagonistic attitude among some of the Mormons towards any who seemed unfriendly to them. A group called the Danites formed, pledging itself to create a righteous community and to protect it. Unfortunately, this attitude stirred up more hard feelings, and the Missourians began to band together, convinced they would have no peace until and unless the Mormons left.

The Danites took other matters into their own hands when they chose to expel dissenters from their community. A few members were tried by the Mormons and were found guilty of selling their land contrary to the revelations Joseph Smith had received (i.e. for their personal gain rather than for the good of the community), had violated the Word of Wisdom, and had tried to undermine Joseph’s authority by falsely accusing him of having committed adultery. These men were found guilty and were excommunicated. The Danites took it upon themselves to expel these men and their families from the community.

Several of the Mormons were upset by this unlawful action, causing more tension within the Church as well as without. While the man principally credited with forming the Danites, Dr. Sampson Avard, is also accused of forming and leading this group to gain personal power, no mention was made of his faults until after things got out of hand. Avard did begin twisting the cause of the group, claiming their members were beyond the reaches of the law and that they should rescue any Danite from governmental trial to be tried instead by their own people. This goes strongly against the teachings of the Church, specifically Article of Faith #12, which states all members of the Church are subject to the government under which they live.

Avard encouraged the Saints to fight back against the Missourians, strengthening his position by telling the members of his secret group his actions were approved by Joseph, which they indisputably were not. The Danites eventually got out of control and began to attack non-Mormon villages. Avard and several others were later excommunicated for their actions.

It is hard to reconcile the Church’s teachings with the actions of individuals or even groups at this time in Church history. While some actions can neither be condoned, nor excused, it is perhaps important to remember how much the Saints had been persecuted and driven; how much they had suffered; how much they had sacrificed. They had been peaceful and had turned the other cheek (Matt. 5:39) many times. They were determined to not be driven any more. They resolved to protect their families and their homes.

After Sidney Rigdon, a prominent Church leader, gave a fiery speech encouraging the Saints to defend themselves against their enemies, members of Carroll County resolved to expel the Mormons for having settled at Dewitt, which many Missourians were upset about. The Carroll County citizens determined to do things as peaceably as possible (though still unlawfully). They seemed to hope by talking about it so much, and through threats of expulsion, the Mormons would just leave. At this time support through most of the state not directly concerned with the issue was inclined to be on the side of the Mormons. Though other citizens sometimes did not have sympathies for the religion itself (or what they had heard the religion was), they still respected the rights offered by the Constitution more than the personal wishes of non-Mormon citizens to not live with Mormons.

In October, Mormon Apostle David W. Patten was killed in a battle along the Crooked River in Ray County. The Mormons had heard an exaggerated story of the kidnapping of some of their members and went to rescue them. Tragically, some were killed on both sides. In turn, exaggerated reports of this battle, along with the actions of the Danites, reached the governor.

Marsh-Hyde Affidavits

The actions of two ex-Mormons increased public agitation even more. Thomas B. Marsh and Orson Hyde, both of whom had been excommunicated from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, were angry and approached government officials with the Marsh-Hyde affidavits stating the alleged dangers of the Mormons as a people. The affidavits also claimed the Mormons intended to take over the state, the country, and eventually the world. On October 24, 1838, three Mormons were captured by the Missourians and a troop was organized to go free them. The group arrived just before dawn and when they were discovered, fighting soon began. Despite the inferior numbers of the Mormons, the Missourians scattered before them, causing both sides to think many of the Missourians had been killed. In fact, the Mormon casualties totaled three dead and seven wounded while the Missourians suffered only one death and six wounded.

After Generals Atchison, Doniphan, and Parks (all of whom had been sympathetic towards the Mormons), heard of the battle, they focused their efforts on protecting innocent Missouri citizens, though they still believed the conflict had been sparked by the Missourians. General Lucas, who was strongly anti-Mormon, informed Governor Boggs that the Missourians would defend any deaths incurred. Soon afterwards, he led troops to march on Far West, where the majority of the Saints now were. During this time, several Mormons were taken prisoner, and horrible treatment of them culminated in many beatings and even deaths.

Governor Boggs’ Extermination Order and Saints’ Surrender at Far West

After exaggerated news, strongly favoring the Missourians’ side, reached Governor Boggs, he was finally roused from his passivity and issued an extermination order on October 27, 1838. It said, in part:

“The Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the State if necessary, for the public peace—their outrages are beyond all description. If you can increase your force, you are authorized to do so, to any extent you may consider necessary.”

Despite the fact that this order was illegal, the spirit of the time embraced it, and all sides were agitated to a peak of fervor. Three days after the order, a mob attacked the village of Haun’s Mill and massacred dozens of men, women, and children, killing at least 17 and wounding 13.

Despite the fact that this order was illegal, the spirit of the time embraced it, and all sides were agitated to a peak of fervor. Three days after the order, a mob attacked the village of Haun’s Mill and massacred dozens of men, women, and children, killing at least 17 and wounding 13.

General Doniphan still attempted negotiations and a peaceful reconciliation. All troops gathered to Far West. Doniphan assured the Saints that Missourians only wished to punish those guilty of plundering, and Joseph Smith appointed Colonel Hinkle and four others to go negotiate a compromise. After hearing of Haun’s Mill, Joseph realized his people would be destroyed if they pursued battle and told Hinkle to sue for mercy.

When Boggs’ orders to run the Saints out arrived, General Lucas met their pleas with a non-negotiable option:

- The Saints would surrender their leaders to be tried and punished.

- The Saints would sign over all of their property to pay for debts incurred by the war.

- The Saints would leave the State with a militia escort to protect them.

- The Saints would surrender all of their arms.

These were the only conditions on which Lucas agreed to spare the Saints. He also required they surrender their leaders within the hour, or the militia would march on Far West. The negotiators returned to Far West and pleaded with the leaders to surrender themselves, which they ultimately decided to do, on October 31. The leaders, however, were under the impression that they would be able to discuss the terms with Lucas. Lucas refused to speak to any of them, and the leaders were tried illegally and sentenced to death. Feeling betrayed, Joseph Smith accused Hinkle and the others of being traitors. It seems they had truly been trying to save the Saints, however, and had given all the facts, as they understood them, to their leaders before they surrendered.

Joseph and other leaders were tried by a court martial and condemned to death. General Alexander Doniphan, a former state legislator and friend to Mormons, refused to allow this sentence to be carried out, declaring that such action would be cold-blooded murder. Moreover, he said, the militia could not condemn Joseph Smith, because he was a civilian and therefore had to be tried before a civilian court. Joseph and other leaders were still imprisoned, though, and were transferred from jail to jail.

After Joseph was taken away, the Mormons were treated worse than ever. Many were dragged from their beds and homes in the night and all were forced to sign over their property to the state — though this was recognized as so obviously illegal, that it was not enforced. The Mormons were allowed to stay until spring, due to the poor weather, but were warned that if they planted crops, they would be killed. Thus all of their property was taken before winter set in. Most did not have homes or adequate shelter, and their future was bleak: they were to be driven from the state as soon as the weather was clear.

Joseph’s Imprisonment

Joseph and the other prisoners were taken to Jackson County, where everyone—on both sides—assumed they would be killed. The prisoners were abused for two weeks before Joseph rebuked the guards for their vulgarities, blasphemies, and obscene jokes. After their trial, Judge King moved Joseph Smith and five of the other prisoners to Liberty Jail in Clay County. Parley P. Pratt and several others remained prisoners in Richmond, and most of the others were released.

Liberty Jail was little more than a dungeon with little heat and in which a man could not even stand upright. For four winter months, the prisoners suffered horrible conditions and were not allowed to lead or even accompany the destitute Saints being driven from Missouri.

Joseph Smith remained in the drafty basement cell of Liberty Jail from November 1838 until April 16, 1839. Overcome for a time with despondency about what had occurred, he prayed fervently. Ultimately he obtained two revelations (Doctrine and Covenants 121 and 122) which brought consolation and counsel. The revelations told him that while he and the Saints had suffered because of their sins, God still accepted them and would help them be successful in the end. Joseph was also reminded of how much the Savior had suffered and was comforted in knowing that the Lord would bless him according to his righteousness.

Joseph and his fellow inmates remained in jail and were repeatedly abused and mistreated. Their appeals for lawyers and even for the right to call witnesses on their behalf were denied. Finally, on April 16, 1839, as they were being led to Columbia, Missouri, the jailer permitted them to escape, realizing they were innocent and would never get a fair trial. They rejoined their families on April 22, 1839, and on May 10 the Mormons moved to Commerce, Hancock County, Illinois, which they renamed Nauvoo.

Expulsion of the Saints from Missouri

![]()

![]()

![]()

Justice was one-sided; only the Mormons were tried and punished for their crimes, and the Missourians were treated as though they had never done anything wrong. While most non-Mormons in the rest of the state argued that expelling them was unconstitutional and that the state had no right to do it, it was the Missourians who had been involved in the conflicts who were given the voice. They wanted the Mormons expelled, and expelled they were going to be. Others in the state called for a thorough investigation of the war, but by January, the Mormons realized they would not be helped by the legislature, and determined to leave as best they could. Most families were destitute, so those who had extra pooled their resources, determining to leave no one behind. Those who had been fortunate enough to retain their property sold it to gain funds with which to leave the state, but they were only able to get a fraction of the properties’ values. The exodus from Missouri took place in the dead of winter, with many Mormons trudging eastward with bare feet and little to keep them warm.

Justice was one-sided; only the Mormons were tried and punished for their crimes, and the Missourians were treated as though they had never done anything wrong. While most non-Mormons in the rest of the state argued that expelling them was unconstitutional and that the state had no right to do it, it was the Missourians who had been involved in the conflicts who were given the voice. They wanted the Mormons expelled, and expelled they were going to be. Others in the state called for a thorough investigation of the war, but by January, the Mormons realized they would not be helped by the legislature, and determined to leave as best they could. Most families were destitute, so those who had extra pooled their resources, determining to leave no one behind. Those who had been fortunate enough to retain their property sold it to gain funds with which to leave the state, but they were only able to get a fraction of the properties’ values. The exodus from Missouri took place in the dead of winter, with many Mormons trudging eastward with bare feet and little to keep them warm.

Many kind people in Quincy, Illinois, took the bedraggled Mormons in, though eventually they were overwhelmed and had to ask the Mormons to leave and impose upon them no longer. Still, such kindness was greatly appreciated by the persecuted and destitute. Eventually the Saints began to settle Commerce, Illinois, yet again building up their own city, which they renamed Nauvoo. They had been forced to leave their homes for the fifth time in less than ten years. Despite all of their hardships, most of the Saints remained faithful and hopeful.

The period of Mormon settlement in, and their ultimate expulsion from, Missouri figures as one of the most tragic periods in the history both of Mormonism and the United States of America. The Mormon Church’s experience in Missouri tested the American commitment to the free exercise of religion, the freedom to vote, and ultimately the ability of a democratic government to protect unpopular minorities.

Two Church Centers: Ohio and Missouri 1835–1837

Joseph Statement of Defense

September 1838 After more persecution, and after the Saints had been driven to the edge of the United States by mobs, Joseph cried out in frustration and determination: “We have been driven time after time, and that without cause; and smitten again and again, and that without provocation; until we have proved the world with […]

Watch a video about the restoration of the gospel on lds.org

Watch a video about the restoration of the gospel on lds.org