The story of the Saluda is strikingly sad, especially when one takes the perspective of William Dunbar, a Scottish convert to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (incorrectly referred to as the “Mormon Church” by the media). In the mid-1800s, Latter-day Saint converts were all travelling West to join the Saints in the Utah Territory. Many would arrive from Europe by ship in New Orleans, then take steamboats to St. Louis, then other steamboats up the Missouri River to Council Bluffs, Iowa (then Kanesville).  There was typically a Church representative in St. Louis to help newly arrived converts gain passage on steamboats for a fair price and get to where they needed to go. However, in 1852, the representative had left and was not replaced until the end of that year. Eli Kelsey and David J. Ross were consequently sent from Kanesville down to St. Louis to help out in the interim. They were also planning to head to the Utah Territory that year, and they felt pressure to get the Saints on their way as quickly as possible. It was still early spring, though, and ice flows in the river were preventing steamboat captains from taking the risk of the journey. When they found Captain Francis T. Belt of the Saluda, he agreed to book passage for about 100 passengers, feeling the profits outweighed the risks he would take. Many of the waiting Saints were grateful, because they were having to pay for unexpected lodging and food during the delay. One of the passengers, William Cameron Dunbar, heard the boat was not the most reliable, so he and two other LDS passengers decided to have a look at the steamboat. Looking back, William said: “on entering the hold a most horrible feeling came over us, and without knowing the cause of it, we had an impression that something awful was going to happen somehow or other.” After leaving the boat, Dunbar remarked, “I remarked to brother Campbell that if I had not already given in my name to go with that steamer, I would not do so now; but under the circumstances we almost felt in duty bound to go, so as not to disappoint the officers of the boat, nor the Elders who had chartered her” (Dunbar account in Jenson, “Church Emigration,” 411).

There was typically a Church representative in St. Louis to help newly arrived converts gain passage on steamboats for a fair price and get to where they needed to go. However, in 1852, the representative had left and was not replaced until the end of that year. Eli Kelsey and David J. Ross were consequently sent from Kanesville down to St. Louis to help out in the interim. They were also planning to head to the Utah Territory that year, and they felt pressure to get the Saints on their way as quickly as possible. It was still early spring, though, and ice flows in the river were preventing steamboat captains from taking the risk of the journey. When they found Captain Francis T. Belt of the Saluda, he agreed to book passage for about 100 passengers, feeling the profits outweighed the risks he would take. Many of the waiting Saints were grateful, because they were having to pay for unexpected lodging and food during the delay. One of the passengers, William Cameron Dunbar, heard the boat was not the most reliable, so he and two other LDS passengers decided to have a look at the steamboat. Looking back, William said: “on entering the hold a most horrible feeling came over us, and without knowing the cause of it, we had an impression that something awful was going to happen somehow or other.” After leaving the boat, Dunbar remarked, “I remarked to brother Campbell that if I had not already given in my name to go with that steamer, I would not do so now; but under the circumstances we almost felt in duty bound to go, so as not to disappoint the officers of the boat, nor the Elders who had chartered her” (Dunbar account in Jenson, “Church Emigration,” 411).  “Although I did not understand it then,” Dunbar later observed, “I am perfectly satisfied now that some friendly unseen power was at work in my behalf, trying to prevent me from going on board with my family on that illfated steamer” (Dunbar account in Jenson, “Church Emigration,” 411).

“Although I did not understand it then,” Dunbar later observed, “I am perfectly satisfied now that some friendly unseen power was at work in my behalf, trying to prevent me from going on board with my family on that illfated steamer” (Dunbar account in Jenson, “Church Emigration,” 411).

Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints believe in the power of the Holy Ghost and His ability to speak to our hearts, guiding us in the direction we should go. Dunbar ignored the prompting he received that he should not go on board. In addition, he could have warned others of his feelings, as could have the other two men who saw the boat with him and felt the same prompting. Dunbar not only ignored the prompting, he also looked over three different delays which could easily have kept his family from being aboard the ship when disaster struck: Supplies he ordered for the journey did not arrive when they were supposed to. He waited for them to be sent down, and then hurried to the dock with his wife and children. They actually missed the boat. They took another boat and tried to catch up with the Saluda, but ice flow and strong river current prevented the two boats from meeting and the passengers to transfer, though they passed each other several times. Finally, the steamboat the Dunbars had managed to take was damaged by ice and the passengers were forced to disembark. William refused to leave, because the captain had promised he would deliver the Dunbars to the Saluda if possible. Ignoring three chances to avoid the Saluda, William finally succeeded in getting his family on board the boat.

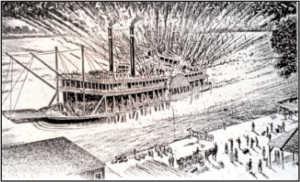

The Saluda had already had an interesting history. It was built in 1846, and had sunk in 1847, remaining underwater for several months. It was raised and floated to St. Louis for repairs, but kept its old boilers. At that time, a six-year-old vessel was quite old for a river boat, when the average life for a steamboat was three to four years, and old boilers were very dangerous. River travel was in and of itself very dangerous. Snags (trees under the water) were common hazards, as were the ice flows. Strong currents were also dangerous. The Saluda had side wheels, which allowed it more maneuverability, but its boilers were still old. The boat reached Lexington, 370 miles from St. Louis, on April 4, but lacked the power to get around Lexington Bend, an infamous horseshoe banking to the left from their position. “Whipping around the point of this bend, the current created a treacherous ‘cross-over’ from the north bank to the south bank along the Lexington bluff. This was the Lexington Bend, a well known hazard to river men of the day” (Dan H. Spies, “The Story of the Saluda,” 2). After admitting defeat the first day, Captain Belt tried again the next day, but ice chunks broke parts of the paddle wheels, and the boat had to be repaired, which took two more days. Many frustrated passengers disembarked because they were close to their destination. This is when the Dunbars were finally able to get aboard the Saluda. Many people, knowing of the Captain’s determination to navigate the bend Friday morning, April 9, went to the bluffs for a good view. Due to the long delay, the Captain was insistent that the boat would make it around the point. According to folklore, Captain Belt said, “I will round the point this morning or blow this boat to hell!” He ordered the engineers to fill the boilers to maximum pressure. The boiler walls were red hot, and before the paddle wheels had made three full revolutions, the boilers exploded. Reports indicate that engineers had let the boilers go dry while they were heating up, so when the cold river water was drawn in, the metal burst. One engineer survived, and admitted this was the case, but also said it the action was under direct orders from the captain.  Witnesses said, “The noise of the explosion resembled the sharp report of thunder, and the houses of the city were shaken as if by the heavings of an earthquake,” causing houses to rattle and windows to shake (“Awful Calamity: Explosion of the Steamer Saluda—130 Lives Lost!!” Liberty Tribune, 16 April 1852, 1). Passengers were thrown into the air and onto the shore. Pieces of the boat’s two tall chimneys, the hurricane deck, the cabin section, and even the boilers flew in all directions. A spectator on the shore was killed by a piece of flying timber. Wreckage fell from the sky and landed as far as 400 yards away. The ship’s 3-foot diameter cast-iron bell and 600-pound safe flew high into the side of the bluffs. Two-thirds of the boat’s structure was destroyed. Many people were thrown into the river. Some survived, many did not. A surprising number suffered only minor injuries, but those closer to the explosion were nearly unidentifiable.

Witnesses said, “The noise of the explosion resembled the sharp report of thunder, and the houses of the city were shaken as if by the heavings of an earthquake,” causing houses to rattle and windows to shake (“Awful Calamity: Explosion of the Steamer Saluda—130 Lives Lost!!” Liberty Tribune, 16 April 1852, 1). Passengers were thrown into the air and onto the shore. Pieces of the boat’s two tall chimneys, the hurricane deck, the cabin section, and even the boilers flew in all directions. A spectator on the shore was killed by a piece of flying timber. Wreckage fell from the sky and landed as far as 400 yards away. The ship’s 3-foot diameter cast-iron bell and 600-pound safe flew high into the side of the bluffs. Two-thirds of the boat’s structure was destroyed. Many people were thrown into the river. Some survived, many did not. A surprising number suffered only minor injuries, but those closer to the explosion were nearly unidentifiable.

William Dunbar had been standing on the deck preparing breakfast. He remembered seeing the paddle wheels rotate twice, then woke up on the river bank. He knew of nothing in between. When he awoke, he saw his dead son lying close to him, but could not move toward him, because his spine had been injured when he was thrown from the boat. He was brought to the hospital, he saw his wife breathe her last breath, but did not have the chance to speak to her. He later saw his daughters remains which were so mangled another woman claimed the child was hers. This memory haunted Dunbar later in life, when he considered the possibility that he had left his daughter an orphan in the town, though he was fairly certain the dead child was his daughter. The total casualties are not precisely known, because so many survivors left almost immediately on another vessel, when its captain offered to take them for free. It is fairly safe to say, though, that between 90 and 100 passengers out of 175 were killed, including crew and passengers. It is estimated that 80 Latter-day Saints who had taken passage aboard the Saluda, 25 were killed, and 3 were missing and presumed dead.

Several of the surviving Saints were injured, and nine were severely injured. Lexington families adopted four orphaned children, including two from Latter-day Saint families. Lexington citizens reached out with true charity to the victims of the Saluda. The created four separate committees to care for the sick, bury the dead, raise money to aid the victims, and find homes for the orphans. Citizens donated $1,000 to pay for related expenses, women cared for the injured and prepared the dead for burial. The city donated a plot of ground for the burials, and twenty-one victims were laid to rest in Christ Church parish cemetery. In addition, citizens gave some survivors money and clothes (many had lost all their belongings) to help them on their journey. Some Saints were cared for, for weeks by Lexington families.

Tragically, some of the surviving Saints from the Saluda died soon thereafter at Kanesville from a cholera epidemic. Others died along the difficult trek to the Salt Lake Valley. Dunbar made it to the Utah Territory and served faithfully in the church for the rest of his life. He remarried and had thirteen children, one of whom he named Helen Euphemia in remembrance of his wife and daughter who died in the explosion.

The explosion of the Saluda and the cholera epidemic of 1852 helped spur reforms and regulations for boat travel, but the next year, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had its members avoid the Missouri River by starting out in Keokuk, 200 miles north of St. Louis. Then, beginning in 1855, LDS immigrants sailed to New York rather than New Orleans, and took much safer railroad travel to the Salt Lake Valley.

Read more about the history of the Saluda.

Watch a video about the restoration of the gospel on lds.org

Watch a video about the restoration of the gospel on lds.org

Its not my first time to pay a quick visit this web page, i am browsing this web site

dailly and take good facts from here daily.

Is there a list of passengers some where?

Hello Ella!

As stated in William G. Hartley’s “‘Dont Go Aboard the Saluda!’: William Dunbar, LDS Emigrants, and Disaster on the Missouri” (http://mormonhistoricsites.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/MHS_Spring2003_Steamboat-Saluda.pdf) only a partial copy of the passenger list survives, which excludes all deck passengers who were onboard at the time.

If you wish to view this partial list, you can find it here: http://www.gendisasters.com/missouri/6189/lexington-mo-steamer-saluda-explosion-apr-1852

I hope this answers your question! Let me know if I can answer any other questions you may have.

– Megan