Parley Pratt remains the most eloquent thus far in describing the atmosphere that pervaded before the coming forth of the Book of Mormon, stating that we “…can never understand precisely what is meant by Restoration, unless we understand what [was] lost or taken away” (Givens, Wrestling the Angel). At the onset of the 19th century, the world was only beginning to see the first signs of dawn.

Born in 1805 and martyred in the summer of 1844, Joseph Smith’s life was firmly rooted in and influenced by the same widespread nationalist fervor, relentless religious upheaval, and profound political divisions that permeated the lives of all during the antebellum era.

But before one attempts to expound upon Smith’s impact upon not only religion, but American culture as a whole, it is important to ground him in the world which he changed; in fact, a deep cultural analysis of Antebellum America can only bring a heightened sense of insight into to our collective understanding of who Joseph Smith would become, both in character and in station.

America Catches Nationalist Fever

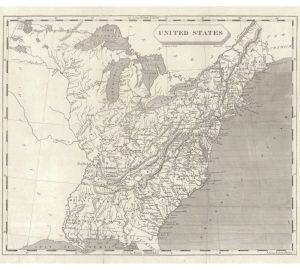

Via Murray Hudson, Halls, Tennessee. A map of the United States at the time of Joseph Smith’s birth in 1805.

A portrait of America in the context of the early 1800’s paints an enticing picture, indeed. A proud, infantile nation stands on wobbling feet as it emerges victorious from two wars.

Its first, the Revolutionary war (1775-1783) bought the nation its ensured autonomy, while the second, the War of 1812 (1812-1815) instilled within its people an unwavering sense of pride.

The birth of an American identity is therefore forever tied with an initial and prevailing sense of nationalism—the exaltation of and devotion to its national culture. Economic nationalism manifested itself as American manufacturing began to find its niche both domestically and in the worldwide market.

The Embargo Act of 1807, a general embargo enacted by the United States Congress against France and Great Britain, stimulated domestic production and encouraged the U.S. to adopt a sense of economic self-reliance. Henry Clay’s “American System”(3)—which touted plans for an industry promoting tariff, a national bank, and federal subsidies for infrastructural development—as well as President James Monroe’s “Era of Good Feelings,” reflected a desire for unity.

However, regionalism, which was simultaneously practiced alongside nationalism, only undermined the goals of Democratic-Republicans such as Monroe. It was this grating tension, particularly between the North and South, that would set the scene for the American Civil War.

A Religious Awakening Begins

The Second Great Awakening took its cues from a long-standing tradition of restorationist movements, some of which can be dated back as early as the Renaissance. Medieval Christian humanism, which emphasized the humanity and personalization of Christ through the study of the Greek New Testament and Hebrew Bible, was fundamental in its impact upon reformers such as John Calvin and Martin Luther, who sought after a “purer” form of Christian belief and practice. (p.24)

The early 19th century brought forth a similar sentiment, as religious orators began to call for a return to a more ideal form of Christian worship. Both English and American religion began to detach itself from its long-held Enlightenment values, which prized—in the vernacular of Mormon scholar Hugh Nibley—the Sophic (logical rationalization without the influence of the supernatural) over the Mantic (faith-based sentiment that readily accepts religious authority).

While historians loosely pin the movement’s beginnings as early as the 1730s, one of its first major events has been referenced as The Cane Ridge Revival held in Cane Ridge, Kentucky, in 1801. The power of religious orators to both compel and spellbind their audiences fanned the flames of theological fervor, catapulting men such as Barton W. Stone (minister of Cane Ridge’s Presbyterian sect) and contemporaries Thomas and Alexander Campell (influential leaders of the Disciples of Christ) to fame.

A shift in morality delivered an immense ripple effect, resulting in the conquest of the abolitionist spirit in upstate New York as well as increased church membership. Many denominations, including The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Shakers, the Seventh Day Adventists, and the Unitarian Universalists, were destined to be born into this revitalized, religiously-charged atmosphere.

The Rise of Print Culture

While Richard M. Hoe’s rotary printing press did not arrive until 1843, its effects on American culture were revolutionary. “Print culture” took form in the popular literature, lithographs, and newspapers that found their way into every pocket. Newspapers, in particular, surged in popularity in the 1830s, when the “penny papers” made both news and literacy all the more accessible to the working class. Sensationalism (as well as the early tabloid) found its origins in this period, as journalists continuously searched for fodder to fill their pages while simultaneously intriguing the masses.

Some of the most paramount achievements of the Antebellum period belonged to the realm of literature. As America was still in its character-forming adolescence, items in print became the basis of its cultural identity, bringing forth literary trends such as Transcendentalism.

Author-philosophers Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau, as well as others involved in the movement each injected their belief in the power of individualism, nature, self-reliance, and progress into their writing. Emerson, whose notable address “American Scholar” was given in 1837, appealed to the budding desire in the States to depart from long-held European traditions and begin to develop a national character. Publication of the Noah Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language was a further attempt at defining the autonomy of the U.S.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, Washington Irving, and Edgar Allen Poe were not only prominent authors of the era, but significantly aided the rise of the short story as a literary genre. Hawthorne, whose renowned novel The Scarlet Letter was an instant best-seller, published shorter works such as the first part of his Twice-Told Tales in 1837.

Washington Irving found his niche in short texts, with tales such as “Rip Van Winkle” (1819) and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (1820) effortlessly becoming part of the American literary canon. The brief narratives and prose of Edgar Allen Poe were similarly well-received, exciting the imaginations of the public between 1832 and 1849. “The Tell-tale Heart,” “The Pit and the Pendulum,” ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” and “The Fall of the House of Usher” each reflected the assertions Poe made in his 1846 essay, “The Philosopy of Composition,” where he argues that texts should not suffer to be long-winded, but rather designed to be enjoyed in a single sitting.

Sickness and Maladies

Despite commercial development, medical knowledge remained relatively rudimentary until after the Civil War. In a BYU History publication, Joseph B. Hinckley cites that there were essentially two methods of medical practice: heroic/allopathic medicine and botanical/homeopathic medicine.

Joseph Smith lived during an epoch referred to as “The Age of Heroic Medicine,” (1780–1850). Heroic (also called allopathic) approaches are defined by treatments with extreme effects, often administered with substantial risk to the patient.

Examples of common practices include bloodletting and the prescription of a castor oil/calomel concoction, which promoted internal “cleansing” to remove toxins and pull disease out of the body. Despite often exacerbating a patient’s ailments rather than acting as a curative, most educated physicians of the time—including Benjamin Rush, whose contributions to American culture included singing the Declaration of Independence—were staunch defendants of this type of medicinal care.

Homeopathic remedies ran their own risks, though perhaps not on the same scale as heroic counterparts. Samuel Thompson, known to history as the Father of American Herbalism, played a vital role in the development of this form of treatment.

Homeopaths such as Thomsonians believed wholeheartedly in the concept of medical liberty, even going so far as to form a political force known as the Popular Health Movement. However, while mild and often alleviatory, herbal remedies with little scientific backing were often powerless against incessant strains of cholera, smallpox, thyphoid, and yellow fever.

Marginalization of the “Other”/Dangerous Divisions

By definition, socio-political tensions dominated the years before the Civil War. The matter of “separate spheres” for both men and women drove the basis for which inequality between the sexes remained.

While white women began to see an increase in educational and vocational opportunities, they were often demeaned and ridiculed for their attempts at merging into “men’s affairs.” Women’s suffrage was, therefore, a pressing issue. So much so, that the discourse inspired by the 1848 Seneca Falls women’s rights convention heavily influenced Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony’s 1881 The History of Women’s Suffrage.

Arm in arm with the division over women’s rights came the turmoil that accompanied the abolitionist movement. In the Antebellum spirit of reform, abolitionists called attention to slavery as yet another damaging, archaic system to turn over.

Numerous arguments to slavery were gaining traction. The Second Great Awakening had shaken America’s moral heart, as Quakers such as Benjamin Lay began to proclaim that slavery should offend any decent Christian’s virtuous sensibilities.

Women such as Angelina Grimke and Sarah Moore Grimke saw the similarities in the persecution of women and African-Americans, and often gave speeches to mixed audiences regarding the absolute need to end slavery. Black abolitionists, such as Fredrick Douglass and Sojourner Truth, brought their own stories as slaves to the forefront, rendering the deeply dehumanizing experience of human bondage as impossible to ignore.

Joseph Smith: America’s Prophet or More?

However central setting may be to the LDS Church’s genesis, Richard Bushman—whose research remains authoritative in studies of the prophet Joseph Smith—advises against restricting his narrative to that of an American venue.

In order to truly understand his contribution to both secular and non-secular realms, Bushman can only advocate a global perspective, stating that it remains “…the only way to highlight the nature of Smith’s achievement…[in tying] him to upstate New York, we will miss the expansiveness of his thinking, like explaining Shakespeare from the small town mentality of Stratford” (Underwood, “Attempting to Situate Joseph Smith“).

Regardless, to seek to understand the culture to which Smith was undoubtedly exposed, and more importantly, the implications of said culture, is not a vain effort; one need only look to the expansive vision that Smith had for his gospel, and the worldwide ripple effect it has since achieved.

In between writing short stories she’ll never finish and marathoning Marvel movies, Megan Finley is often found missing the loves of her life, her two cats Leia and Loki. Her passion for “geek culture” extends into her passion for academics, as she is an optimistic MA student with plans to be the next Professor X (with hair). Her life’s dream is a simple one—to drink a hot chocolate in every Disney park in the world.

Watch a video about the restoration of the gospel on lds.org

Watch a video about the restoration of the gospel on lds.org

Many people try to look at history through their current cultural eyes. I appreciate how this article provides some context and cultural background of the period of time Joseph Smith was a part of. While there are plenty of accounts that either laud his accomplishments, or expose his foibles, we need to see everything in the proper context. Thank you for your efforts to set a solid foundation.

Rob,

Thank you for reading! Your encouraging comments were a wonderful boost to my day.

All Best,

Megan