This article titled “The Quincy Miracle: How One Town Saved Thousands of Mormon Refugees” by Glenn Rawson appeared in the 19 Movember 2016 edition of LDS Living.com.

On October 27, 1838, Missouri governor Lilburn W. Boggs issued an extermination order forcing thousands of Latter-day Saints to leave Missouri by March 8, 1839, or be killed. But where could they go?

“The Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the state if necessary for the public peace,” Executive Order 44 declared. Thousands of Missouri militia forces were called out; they surrounded the Latter-day Saint settlement of Far West and demanded that the Mormons leave the state according to the governor’s order.

But where could more than 10,000 people go on a moment’s notice as winter approached? They were already on the western frontier of the United States. They couldn’t go south; that would take them deeper into Missouri. They couldn’t go west; that was Indian Territory. They couldn’t go north; that was Iowa Territory, which was sparsely settled at best. The shortest and most direct route out of Missouri was due east, across the Mississippi River and into Illinois. Based on invitations from a few Church members already living in Quincy, Illinois, it was decided that the main body of the Latter-day Saints would join the handful already in the town.

To hasten the Mormons’ departure, mobs continued to prey on them, plundering, pillaging, raping, and burning. Joseph and Hyrum Smith were taken prisoner along with other Church leaders, and it was announced that they would be held until every Mormon had left the state. Joseph Holbrook commented, “We found that there was no more peace or safety for the saints in the state of Missouri. If the Church would make haste and move as fast as possible, it would aid much to relieve our brethren who are now in jail as our enemies were determined to hold them as hostages until the Church left the state. Every exertion was made in the dead of winter to remove as fast as possible” (Pamela Call Johnson, Joseph Holbrook, Mormon Pioneer, Journal).

By December 1838, the Mormons began to move with whatever conveyance they could obtain, leaving behind much of what they owned. Brigham Young invited the Mormon brethren to covenant to assist the poor in leaving the state, and he did his best to gather resources to help them leave. He would not rest until all were safely out of Missouri.

By the bitter cold of January 1839, there were hundreds of men, women, and children strung along a 200-mile trail leading east. The weather was forbidding. At times the snow fell as much as a foot deep, accompanied by wind and bitter cold. At other times their way was marred by rain and deep mud. None had adequate food or clothing. Some were barefoot—their way across the prairie was marked by bloody footprints. Not all would survive the flight from Missouri. And Joseph Smith Sr., who became ill during the exodus to Quincy, would die later in Nauvoo because of it.

By February, hundreds of Mormon refugees lined the west bank of the Mississippi River. Wagons filled with families and all they owned would pull to the river’s edge, drop their human cargo and their meager belongings in the snow before turning back to help evacuate more of their fellow Saints.

At times the mighty river was impassable, as large chunks of floating ice prevented boat traffic on the river. Under these conditions, the Mormons were trapped: ahead was the impenetrable river, and behind were the Missourians, terrorizing them at every turn. Their only option was to hunker down and wait for the river to freeze so that they could cross over to Illinois on the ice.

Meanwhile, from across the river, citizens of Quincy saw firsthand the miserable drama of human suffering. The Quincy Whig documented, “A large number of families are encamped on the opposite bank of the Mississippi waiting for an opportunity to cross. . . . If they have been thrown upon our shores destitute, through the oppressive people of Missouri, common humanity must oblige us to aid and relieve them all in our power.”

Sometimes the shelter for the refugees consisted of nothing more than a blanket thrown over a low-hanging limb. It was under these conditions that one Latter-day Saint woman, Martha Thomas, gave birth in a bed comprised of a rope contraption under quilts hung over a tree.

Notwithstanding the risk, a delegation of Quincy residents braved their way across the river, bringing blankets and supplies. When they inquired of the Mormons what they needed, they were told:

“If we should say what our present wants are, it would be beyond all calculation, as we have been robbed of our corn, wheat, horses, cattle, hogs, wearing apparel, houses and homes, and indeed of all that renders life tolerable. . . . Give us employment. Rent us farms. And allow us the protection and privileges of other citizens” (Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976 reprint), 3:269–70).

The river alternately froze and thawed throughout January and February. In late February 1839, the temperature dropped and the river froze solid. The Mormons still stuck on the Missouri side braved the ice and crossed. Eleven-year-old Mosiah Hancock talked of struggling to walk across the clear and slippery ice barefoot. As he neared the eastern bank, the ice began to break up.

“Father said, ‘Run Mosiah!’ and I did run,” the boy remembered. “We all just made it on the opposite bank when the ice started to snap and pile up in great heaps and the water broke through” (Mosiah Hancock, Autobiography).

The relief Mormons felt after finally being free of the terrors of Missouri was so great that some dropped to their knees on Quincy’s shores and offered prayers of thanksgiving; others kissed the ground. Some made camp on the banks of the river while others struggled up the bluffs to Washington Park, the main square of Quincy, where they set up makeshift tents. Wilford Woodruff described the following scene:

“I saw a great many of the saints, old and young, lying in the mud and water, in a rainstorm, without tent or covering. . . . The sight filled my eyes with tears” (“Wilford Woodruff History, from His Own Pen,” Millennial Star).

The citizens of Quincy had compassion on the beleaguered Saints, especially the suffering women and children, and determined to take them in. The cry for compassion was led by Quincy’s mayor and founder, John Wood.

Orville Browning, another of Quincy’s leading sons and an eyewitness of the Saints’ suffering, declared, “Great God! Have I not seen it? Yes, my eyes have beheld the blood stained traces of innocent women and children in the drear winter, who had traveled hundreds of miles barefoot through frost and snow, to seek refuge from their savage pursuers” (History of the Church, 4:368).

Compassion overwhelmed the people of Quincy, and as they had done before and would do again, they took in the homeless and ministered to the suffering. They brought the Mormons into their homes, shops, and even their barns. Every space that could be made hospitable was opened to the suffering Saints. The Mormons filled Quincy to overflowing before spreading out into other communities in Adams County. John Lowe Butler described the kindness that so typified the people of Quincy:

“The old gentleman came to me and told me to bring my family up to one of his houses and we could live in it until we had been there a little while so that we should have a little time to look about us and get a place. . . . He never charged us anything for what we had. There were three or four other families living close to us that were Mormons. They were living in his houses that were joining ours. He treated them all with kindness. It seemed a new thing to us to be treated with so much kindness” (John L. Butler, “A History of the Biography of John L. Butler”).

The small community of Quincy, numbering fewer than 2,000 people, somehow absorbed more than 5,000 Mormons, giving them not only shelter but also food, clothing, and jobs. When the Quincy citizens couldn’t provide any more from their own stores, they sent out pleas for assistance as far away as Washington, D.C.

The Mormons would never forget what was done and by whom. A statement by the First Presidency proclaimed, “It would be impossible to enumerate all those who in our time of deep distress, nobly came forward to our relief and like the Good Samaritan poured oil into our wounds and contributed liberally to our necessities” (“Proclamation to the Saints Scattered Abroad, January 15, 1841,” History of the Church).

In April 1839, Joseph Smith escaped prison in Missouri and found his way to his family in Quincy.

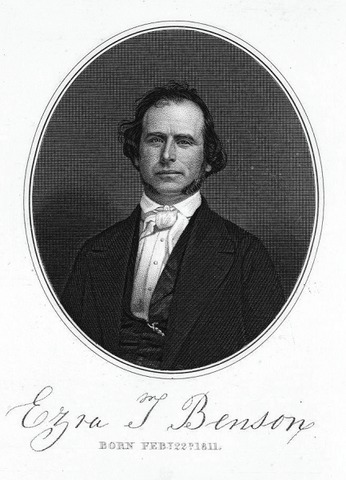

For the brief period of three months, Quincy, Illinois, was the headquarters of the Latter-day Saints. Some of the Saints made their homes among the good people of Quincy. Some citizens of Quincy—including Ezra T. Benson, great-grandfather of President Ezra Taft Benson—joined the Mormons and traveled on with them.

By May 1839, Joseph Smith and the first wave of Saints had moved 50 miles north of Quincy to Commerce, where they began building the foundations of a new city that would later be called Nauvoo. All but a handful of Mormons eventually left Quincy and settled in Nauvoo or other places in Hancock County.

But the miraculous kindness of Quincy didn’t stop there. Seven years later, in the fall of 1846, when the Mormons left Illinois for a new home in the Rocky Mountains, it was the citizens of Quincy who rallied. They loaded barges with food, clothing, and supplies, sailing the Saints up-river and aiding even the poorest of the Mormons in their exodus to the West.

The legacy of Quincy will endure as one of great humanitarian compassion. The deeds of Quincy’s citizenry will live forever in the hearts of many who descended from those Mormons sheltered and saved in Quincy in 1839. Joseph Smith himself summed up the deeds of Quincy’s citizens and their place in history: “They burst the chains of slavery and proclaimed us forever free! Quincy, our first noble city of refuge when we came from the slaughter in Missouri and with our garments stained with blood, should not be forgotten” (History of the Church, 4:292).

Lead image by Julie Rogers (courtesy of Glenn Rawson).

Watch a video about the restoration of the gospel on lds.org

Watch a video about the restoration of the gospel on lds.org