This article was written by Russell Stevenson and appeared on LDS.net on 30 March 2016.

David Todd Christofferson strode down the sidewalk with the judge, discussing matters that would change America’s political future for the foreseeable future.

Born in Utah County, Todd lived in Pleasant Grove and Lindon until age 15. While still a young man, he moved to New Brunswick and then Somerset, New Jersey, yet another suburb in the wave of housing developments built following World War II.

Christofferson credits his future success, in part, to the inspirational role of a woman in his local congregation, Anna Daines, one of the stalwart members of the Church in New Jersey. “Sister Daines took notice of me and often expressed confidence in my abilities and potential, which inspired me to reach high—higher than I would have without her encouragement.”

People should not “discount the power,” Christofferson recalled of his youth, “that good example can provide. . . you think back and remember, ‘they were strong. I can be strong.’”1 Decades later, Christofferson has looked back, observing that he has been “remarkably blessed” by his mother’s moral influence, also. 2

Family Men

Christofferson was a Mormon baby boomer par excellence: clean-cut, mentally exacting, and dogged. After graduating from Franklin High School, Todd returned to his Utah County birthplace to attend Brigham Young University. While running crowd control at a BYU football game, Katherine Jacob, a pretty member of the Cougarettes (BYU’s formation dancing troupe), caught his eye: “That face stuck in my mind,” he remembered. Todd scoured the next year’s yearbook, and—BYU being the relatively tight-knit community that it was—had a mutual friend set up the date.3 The pair married in April 1968 and traveled cross country for the next chapter.

Accepted into Duke University, one of the nation’s most prestigious law schools, Todd’s future teemed with hope. Walter E. Dellinger, an associate law professor at Duke University (now, the Douglas B. Maggs Emeritus Professor) considered the young Mormon to be “a bright and able law student of exemplary character and refreshing personality.” Quick on his feet, Dellinger declared Todd’s skills of articulation to be exemplary: “one of the best students at oral advocacy that I have seen.” Better still, Todd’s manner was pleasant: “while. . .calm and deliberate, his mind is precise and his reasoning clear.” Christofferson had been “a delightful person with whom to work.”4

In summer 1971, he took work as a summer associate at the law firm in Cleveland; partner C. Richard Brubaker commended Todd as “one of the finest young men I have ever had the opportunity to be associated with. . .mature, intelligent, self-reliant, industrious, and responsible.”5 He had also served on the editorial board of the Duke Law Review and as the Academics Vice-President of the Associated Students of BYU. That Todd had the talent and charisma for leadership was apparent to all.

He left BYU during a year of events that racked the nation. Over the course of a few months, both Martin Luther King, Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated. Christofferson arrived on a campus that, while mild by comparison to universities such as University of California-Berkeley or New York University, exuded an atmosphere of discontent. That April, students had marched to declare that “we are all implicated” in the death of Dr. King. But the protest proved to be one that sought to uphold—rather than dismantle—the system. As one participant in the protests observed, “Duke administrators were good men in bad positions who just need to be educated.”6 Christofferson was a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Army Reserve and had little interest in the protest movements, Woodstocks or orgies that engaged other young adults.

While Christofferson worked his way through law school, Katherine Jacob Christofferson gave birth to their young child, Todd Andrew. Christofferson recalled the birth to be a “sacred experience,” though he later joked that he could hear his wife retort: “Easy for you to say. You weren’t the one in pain.” Those who knew her, Christofferson observed, could easily say that he “married much above myself, a conclusion I heartily agree with.” Kathy has downplayed her efforts, saying that “when we grew up, society at large was more likely to support moral behavior than it is now.” She credited her youth bishop as “wonderful and influential in those critical teen years” to “sit down with each one of us individually and really talk about those moral decisions that we need to make,” to emphasize that “we needed to be strong, and it was worth it.”7

In fall 1971, Todd started to seek out clerkships. Chief Judge John Sirica of the Washington, D.C. district court announced an opening. Todd submitted his application package in September, hoping for the best. Todd offered to come to Washington on October 21-22 “at which time I would be available for an interview at your convenience.”8 When the Judge met Todd, they hit it off immediately. The Judge arranged for Todd to meet his wife and children.

Christofferson found the possibilities inspiring: “Although I had imagined it to be an appealing opportunity, the position sounded even more inviting than I had supposed.” He was “more anxious than ever to be considered for the clerkship.” Todd made no secret of his aspirations: “Quite frankly, there is nothing I would prefer more than to be selected.”9 Sirica, Todd told Sirica’s aide, Michael Ryan, is “the sort of person you like and admire immediately.” Sirica “would make hard work feel good”—a feeling that rang true for this child of twentieth-century Mormonism who had been trained to appreciate and uphold institutions, bureaucracy, and the System.10

Sirica found Christofferson equally compelling. It was not his first brush with a Mormon; he had been a good friend of Jack Dempsey, the heavyweight champion and a lax Mormon. Meanwhile, Christofferson was a family man—and “happily so.”11 Sirica—with a little bashfulness—had urged Christofferson to encourage his son, Jack, a new freshman at Duke. “I wish I didn’t have to bother you with a personal matter,” Sirica admitted. “As a parent yourself, you can imagine that it is a great relief to Mrs. Sirica and me to have someone like you with your background and experience near our youngster.” While they trusted Jack to do well in college, “that extra bit of encouragement can really help.”12

Christofferson acknowledged the strength of the competition., “An abundance of qualified persons” had surely applied, but he urged Sirica to “find my application worthy of strong consideration in reaching your decision.” Christofferson read his competition well; over 200 applicants had applied. In November, Sirica made his choice: Christofferson was his man. He surely had “the necessary intellectual and personal qualities to enable him to handle the demands of the job.” Sirica hired the new attorney for the standard term: a year, starting in September 1972 and lasting until September 1973. Sirica and Christofferson were expecting a rather typical year in the D.C. District Court, but it was not to be. Instead, Christofferson enjoyed a “ringside seat” to one of the great political epochs in American history.13

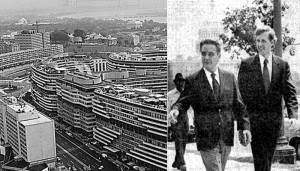

Judge Sirica and Todd Christofferson; “Dean Sentenced to 1 to 4 Years in Cover-up Case,” Washington Post, August 3, 1974, 53.

Dirty Tricks

For years, Nixon had shown his willingness to deploy “dirty tricks” in order to win political advantage. When Lyndon B. Johnson was negotiating with South Vietnam to end the Vietnam War, Nixon sent a backchannel diplomat telling the South Vietnamese to hold out, that he would secure a better deal for them. In 1970, Daniel Ellsberg, a Department of Defense operative, leaked the Pentagon Papers—a series of internal documents detailing the ongoing failures of America’s Vietnam strategies.

The next year, Mormon journalist Jack Anderson used a fellow Mormon connection to acquire documents revealing Nixon’s pro-Pakistan slant in the India-Pakistan conflict. In the midst of this ongoing flurry of leaks and revelations, Nixon established what came to be known as a “Plumbers” unit to fix the leaks: “Do whatever has to be done to stop these leaks,” he told aide Charles Colson, “and prevent further disclosures. I don’t want to be told why it can’t be done. This government cannot survive, it cannot function, if anyone can run out and leak whatever documents he wants to…I want it done, whatever the cost.”14

In the spirit of Nixon’s order, Attorney General John Mitchell and Special Assistant Jeb Magruder formed CRP: the Committee to Re-Elect the President. Mitchell resigned from his post as Attorney General to serve as campaign manager for Nixon’s re-election. The Committee sprawled throughout the Nixon administration and the private sector, ranging from White House Aide Charles Colson (who, in sobriety, had suggested firebombing the Brookings Institution) to Attorney General John Mitchell.

A Day in the Spa

CRP head Francis L. Dale, owner of the Cincinnati Reds, loved a good spa day; it enabled unimpeded conversation beyond the ever-listening ear of FBI tapping devices. Nothing promoted an environment of brotherly support like men sitting around in towels as they talked about tactics, enemies, anti-war protestors, and annoying journalists.15

Historian Gary Wills has observed that Nixon had no master plan for corruption: “Nixon’s vindictiveness was petty and ill-aimed and ultimately self-defeating. He was clumsy at everything else, why not at crime?”16 But what it lacked in organization, the CRP made up for in its willingness to engage in violence.

The plot against Mormon journalist Jack Anderson reveals the extent to which the CRP would break laws to protect Nixon from criticism. By now, Anderson had a nasty reputation for revealing classified information through his Washington Postcolumn. White House aide, Charles Colson, harbored no reservations about unleashing his operatives on the Mormon muckraker. Colson informed Hunt that silencing Anderson was “very important” and that he was “authorized to do whatever was necessary” to carry out the deed. After Hunt contacted Liddy about the task, they “examined all the alternatives and very quickly came to the conclusion [that] the only way you’re going to be able to stop him is to kill him.” Liddy bragged that he “could kill a man with a pencil in a matter of seconds.”

But that was too messy.

The men reached out to Dr. Edward Gunn, a medical consultant for the CIA known for his “unorthodox application of medical and chemical knowledge” and a former collaborator in the Bay of Pigs overthrow attempt. Gunn later recalled the men claiming that “they had an individual who was giving them trouble,” and they “wanted something that would get him out of the way.”

Perhaps applying LSD to the steering wheel to cause a fatal accident? Too risky; Anderson’s wife or children might drive the car, and wearing gloves would prevent full absorption of the drug. Arrange an auto collision with another vehicle? Too involved; a trained collision operative “might not be available.” The CIA was stingy with their resources, and then they could use their request as leverage against them later.

Couldn’t they just get the Cubans to do it? It would make things simpler for the CRP operatives trying to keep their hands clean, but Anderson’s network proved too expansive even for them; Anderson personally knew some of the proposed Cuban assassins, and one had even stayed with the Andersons as a friendly houseguest. Eager, Liddy was willing to take extreme measures: “I know it violates the sensibilities of the innocent and tender-minded,” he observed, “but in the real world, you sometimes have to employ extreme and extralegal methods to preserve the very system whose laws you’re violating.”17 Finally, the White House informed Hunt that the operation was no longer worth the trouble. Anderson’s revelations had lost their punch, and the White House had an election to win.

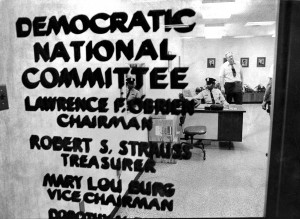

The Watergate break-in was another piece in a sprawling, disorganized system of violence and corruption that swirled around the Oval Office. On May 27, a team of burglars, led by CRP operative, G. Gordon Liddy, broke into the Watergate Hotel, the site of the Democratic National Party Headquarters, to install phone bugs. Nearly three weeks later, on June 17, Liddy ordered a second break-in. The context, circumstances, and rationales for the break-in are among the most speculated, discussed, and dissected in twentieth-century American history. The second band of men consisted of Cuban refugees and former intelligence men who had devoted themselves to Republican party politics for the past decade: Bernard Barker was a Florida realtor and former CIA officer; Virgilio R. Gonzalez, a Cuban locksmith; James McCord, a former FBI agent; Eugenio R. Martinez and Frank Sturgis, both employees of Barker’s. All of the men, to some extent, had collaborated with the failed invasion of Cuba during the John F. Kennedy administration. No evidence has surfaced suggesting that Nixon ordered the Watergate break-ins.

What did the burglars want? Dirt. Debates have swirled about what exactly the burglars were trying to dig up. A chorus of historians and journalists have argued that the burglars were looking to acquire intelligence on prominent Democrats’ solicitation of prostitutes, ranging from Democratic National Chairman Lawrence O’Brien to R. Spencer Oliver to Maxene Wells. Others pointed to O’Brien’s dealings with eccentric billionaire and Vegas tycoon, Howard Hughes. Maybe they could prove that O’Brien was psychologically unstable.

Yet for all their hopes of obtaining salacious details about the night-lives of Democratic operatives, the operation became a comic spectacle in utterly buffoonish incompetence. In order to keep the office door open during their entrances and exits, they left a piece of tape on the doors to offices from the first to eighth floors. Frank Wills, an African-American security guard, noticed it during his rounds, assuming that a janitor had placed it there. He removed the tape, only to find it there again on his second pass. As one of the burglars remembered: “Soon we started hearing noises. People going up and down. . .then there was running and men shouting: ‘Come out with your hands up or we will shoot!’ and things like that.”18 When a journalist asked White House Press Secretary Ronald Ziegler about the incident, he dismissed it as nothing more than a “second-rate burglary.”19

Only two weeks later, John Mitchell resigned from the committee, citing family considerations: “They have patiently put up with my long absences for some four years and the moment has come when I must devote more time to them.”20

“Those times,” CRP operative John Caulfied recalled, “were days of madness.”21

Someone Will Talk

On September 15, 1972—two weeks after the start of Christofferson’s term as Sirica’s clerk—the men in both burglaries were indicted in Sirica’s court on charges of burglary, but all were released on bail. Health issues affecting Sirica delayed the start of the trial. Then, shortly after the trial began in January, five of the seven defendants plead guilty. Sirica thought the guilty pleas were part of a cover-up, but there was nothing he could do to prove it. The trial continued with James McCord and Gordon Liddy, both of whom were convicted. Frustrated at what he thought was a cover-up and even possible perjury during the trial, Sirica told Christofferson—and himself: “Someone will talk. Someone will talk.”22

In March 1973, McCord broke his silence. On March 20, Richard Azzaro, a law student and part-time law clerk, was “seated. . .with Todd Christofferson” when he “heard the door open and observed Mr. McCord standing in the reception room.” Azzaro “identified him by name, alerted Mr. Christofferson to Mr. McCord’s presence and I proceeded to talk with him in the reception room.” McCord handed Azzaro two white envelopes. Sirica refused to communicate with any parties in ongoing litigation; he should communicate with either his lawyer or probation officer. McCord gave the letters to his parole officer, Mr. Morgan, who passed them to Sirica.23

Sirica read the contents in a closed court with Christofferson and Azzaro present, as well as McCord’s parole officer and Nicholas Sokal, the court reporter. After deciding to have the letters “taped and sealed and the transcribed part of these proceedings today” Sirica asked Christofferson if he had anything to add. Christofferson affirmed Sirica’s decision: “I think you are right, Judge. It ought to be held without any further disclosure at this time.”24 Christofferson encouraged Sirica to “on the record instruct each of us to keep it confidential.”25 At the appropriate time, Sirica delivered the McCord letter to the prosecutors for consideration by the Grand Jury. Meanwhile, Nixon actively attempted to stop the investigation. “I want you all to stonewall it,” Nixon said. “Let them plead the Fifth Amendment, cover-up or anything else, if it’ll save it—save the plan.”26

Reporters found Sirica and Christofferson to be an odd pair. They were “two men vastly unlike in backgrounds.” Whereas Christofferson “does not smoke or drink,” Sirica “grew up in rough-and-tumble circumstances.”27 Mormon author Eugene England placed Christofferson in a long line of honorable Mormons involved in Watergate, including Utah Congressman Wayne Owens, journalist Jack Anderson, and Utah Senator Wallace Bennett. Christofferson showed “a steady, courageous integrity to basic Gospel principles concerning the proper relationships between freedom and authoritative leadership.” Indeed, England observed, “some of the most dangerous people during this time have been those who, with religious intensity, arrogated to themselves—or their leaders—the unique power to rescue the country. . .and in tragic pride destroyed the rule of law in order to ‘save’ it.“28

A Very Sad Experience

With McCord’s letters in hand, the Grand Jury began to issue subpoenas to the White House. That April, Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman, White House Aide John Erlichman and Attorney General Richard Kleindienst resigned. In February 1973, Senator Edward Kennedy presented a resolution to form an ad hoc Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities. North Carolina Senator Sam Ervin served as chair, and a special prosecutor, former Solicitor General and Harvard Law Professor Archibald Cox, was appointed to oversee the prosecution of Watergate perpetrators.

Between the investigations of Cox and the Senate committee, documents surfaced revealing that Erlichman had known about the Plumbers breaking into the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist; one Plumber, Egil Krogh, penned a memo saying that “a covert operation be undertaken to examine all of the medical files still held by Ellsberg’s psychiatrist.” Erlichman wrote on the memo: “if done under your assurance that it is not traceable.”29 Months later, Vice President Spiro T. Agrew resigned under prosecution for tax fraud; Nixon appointed Representative Gerald R. Ford to replace him.

In July ‘73, former presidential secretary Alexander Butterfield revealed in testimony to the Senate Select Committee that a voice-activated recording system existed in the White House, a revelation that broke the case wide open. Cox, on behalf of the Grand Jury and the Senate Committee, asked Sirica to enforce their subpoenas to Nixon for the tapes for review. Nixon resisted, citing executive privilege. Sirica finally ruled that Nixon must turn over the tapes for screening in camera by the court prior to delivering relevant portions to the Special Prosecutor. He directed Christofferson to write up an opinion: “It was one of those moments,” Christofferson recalled, “when you were glad to be in the legal profession.”30 After all, Sirica asked, “what distinctive quality of the presidency permits its incumbent to withhold evidence?”31

But Nixon refused, citing executive privilege. He appealed the decision to the United States Court of Appeals, arguing that Sirica’s order posed a threat to “the continued existence of the Presidency as a functioning institution.”32 The Court of Appeals found the case to be unusual, to say the least: “a unique inter-meshing of events unlikely soon, if ever, to recur.”33 The Court of Appeals issued a confusing ruling: the two sides needed to resolve their differences, or the court would issue a binding ruling. Cox offered Nixon a compromise: the White House could release transcripts they thought relevant, and the tapes could be reviewed by an outside party. Again, Nixon defied the order.

Frustrated, Cox threatened charging Nixon with obstructing justice unless he turned over the reels. Nixon then ordered Attorney General Elliot Richardson to fire Cox. Richardson refused—and resigned. Nixon ordered Deputy Attorney General William D. Ruckleshaus to fire Cox; he also resigned. Solicitor General Robert Bork finally agreed to carry Nixon’s order. The personnel shake-up entered the press as the “Saturday Night Massacre.” Further confounding the investigation, Nixon appointed Francis Dale to his representative to the United Nations, removing him from the public eye.

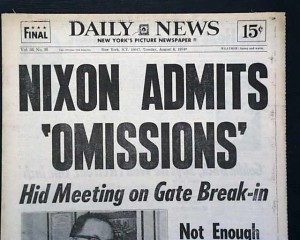

In the face of a public uproar, Nixon appointed Leon Jaworski as the new prosecutor in November 1973, and Nixon finally delivered the subpoenaed tapes to Judge Sirica for his review in camera. On April 16, 1974, Jaworski requested a new subpoena for additional tapes. This time, after Sirica ordered Nixon to comply with the new subpoena, the case went up on appeal directly to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court determined that “it cannot be concluded that the District Court erred in ordering in camera examination of the subpoenaed material.”34

Adding to the drama was Secretary Rose Mary Wood’s “terrible mistake,” as she testified: she had erased 18 ½ minutes of conversation from the June 20, 1972 reel.35 When she was asked to demonstrate how such a “mistake” could occur, she revealed an erasure could have only occurred if she had stretched both an arm and a leg in opposite directions to press control buttons simultaneously (a ridiculous looking contortion that the press designated the “Rose Mary Stretch”). Indeed, numerous studies have confirmed that the erased portion consisted of a series of erasures, rendering it to be a deliberate choice.

When Sirica began the process of reviewing the White House tapes in December 1973, he did not listen alone. Todd Christofferson sat beside him, both of them using earphones. “At first,” Sirica wrote, “it was a stunning experience.”36 Cloistered in the jury room by his office, the two men sat the same table where the jury had found the burglars guilty. The two men took meticulous care to protect the integrity of the tapes. Christofferson “stuffed paper under the record key to prevent any accidental erasures.” With the profound silence of the jury room surrounding them, the voices of the President and his aides gave the illusion of their presence. “It was the first time in history that someone other than the president and his aides themselves had so intimate a view of the innermost workings of an American executive and his staff.”37

The tapes were damning. Christofferson and Sirica first noticed that Nixon had a mouth, and even the hard-scrabble Judge found himself shocked by his language. “The contrast between the coarse, private Nixon speech and the utterly correct public Nixon” disoriented him. Worse, he heard for himself the President’s total lack of interest “to clean up the mess.” The experience rattled the judge: “It was one of the most disillusioning experiences of my life to have to listen now to what had gone on at highest levels of the government of the United States.”38 When Prosecutor Leon Jaworksi heard the same tape, he felt “badly shaken, so shaken that I didn’t want anyone to notice it.” After retiring to his room, his mind popped with activity: “My brain was acting like a ticker-tape. My thoughts were clear, but they ran through my mind without break, one becoming another and then quickly another.”39

The tapes revealed that Nixon had known about his operatives’ involvement in the burglary from the beginning, and they had actively collaborated to prevent the government from prosecuting the criminals. John Dean, Nixon’s personal legal counsel, went on record warning the President that there is “a cancer growing on the presidency,” and that it would soon become all-consuming. Worse, Howard Hunt and others threatened to go public with their connections to the White House if they did not receive a bribe.

Christofferson expected Nixon to explode: “What?’ People are trying to blackmail me? To blackmail the President of the United States in this office? I won’t hear of it.” Instead, the President calmly asked Dean how much money it would take to keep them silent, observing that it would not be a problem to raise the money. When Christofferson heard the President say these things, he felt as though he had been “hit in the gut” and struggled to breathe. Christofferson had voted for Nixon twice, in 1968 and 1972.40 “I was pulling for Nixon,” Christofferson admitted. But after hearing that tape, he felt “dumbfounded, disappointed, shattered.” Their work was clouded in malaise: “We kind of stared at each other. . .didn’t feel like saying much. . . went home early. . . .didn’t feel like working much.” It was all “a very sad experience.”41

The Only One I Could Talk With

American anxiety over the Watergate episode struck global leaders as overly-sensitive. Soviet ambassador Anatoly Dobrinin wondered: “How could the most powerful person in the United States, the most important person in the world, be legally forced to step down for stealing some silly documents?” Compelling a world leader to be “removed by legal means” was “contrary to the mentality” of Soviet leadership.42 British media outlets exhausted their viewers with coverage: “American politics had always been corrupt,” many viewers felt. “Let America clear up its own mess.”43 In France, government wiretapping had come to the fore of public debate; members of Parliament hoped to model itself after Sirica and the Senate committee to address its own issue of “Wategate-on-the-Seine.”44

Christofferson communicated with politicians, and at Sirica’s request, he handled press inquiries.45 Christofferson acknowledged that both he and Sirica were “real babes in the woods as far as the press was concerned and learned a lot very quickly.” While judges typically ban their clerks from speaking to the press, Sirica found the whole circus exhausting, advising Christofferson: “Look, you deal with them. That’s your job.”46

The new Special Prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, with the relevant tapes in hand, pursued new indictments against those who had instigated the Watergate “cover-up.” Action unfolded on a daily basis. When a grand jury handed Sirica a 50-page report that, essentially, indicted Nixon on several counts, Sirica directed that it be turned over to the House Impeachment Committee. Christofferson personally delivered the report in a large briefcase to the committee chairman, Peter Rodino, at the Capitol. That August, Nixon resigned from office, even as articles of impeachment were about to be passed in the House of Representatives. For his efforts, Sirica was named Timemagazine’s Man of the Year for 1973.47

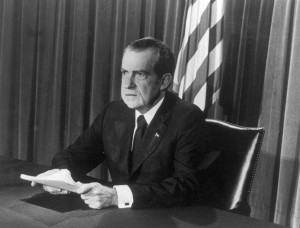

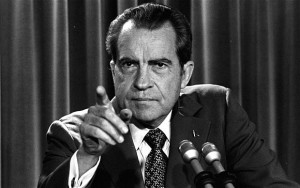

U.S. President Richard M. Nixon sits at a desk, holding papers, as he announces his resignation on television, Washington, D.C. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

At Sirica’s request, Christofferson served as his clerk for an extra 16 months. In January 1975, he moved on from the whirlwind of Watergate, served his active duty Army commitment, and began work at a Washington law firm. In March 1976, at the age of 31, he became a bishop for his local ward. In 1979, Sirica produced his own memoir of “those hectic days” of Watergate, and he thanked Christofferson immensely for his “aid and support during those difficult days of the trials and hearings.” Christofferson was “the only one I could talk to,” Sirica told Associated Press.48 “Without his help and advice and patience and everything else, it would have been pretty difficult for me in making these awesome decisions.”49Christofferson thought little of his contribution; he was in “the right place at the right time,” and nothing more.

What Protects Us

The experience taught Christofferson “crucial life lessons” about public morality and the line dividing the “good men” from the “bad.” More, Christofferson asked, “what is it that caused or permitted them [Nixon and his advisors] to go seriously off-track?” Christofferson wondered. They were “basically good and decent family men.” When Nixon chatted with his daughter, Julie, he heard “a wonderfully normal, affectionate father., . .they were just family, and by the expressions, tone, and feelings reflected in their voices, a happy and healthy family.” And if Nixon and his men were, essentially like us, Christofferson wondered, “what protects you or me, in our marriages, family life, and professional and vocational endeavors, from tragically destructive errors or even criminal conduct?”50

The Watergate scandal represented an administration-wide lapse in conscience, Christofferson has observed. When Nixon was told that the Watergate burglars demanded hush money, he could have said, ‘No, it goes no further. Let the chips fall where they may.’ And he didn’t, and it mushroomed. That one failing brought the whole house down.” Nixon “put his integrity on hold,” and in so doing, he put himself “in danger of of losing the benefit and protection of conscience altogether.” Christofferson lauds the work of myriad public servants to fight Nixon’s corruption. At “close range,” he “witnessed what lawyers of skill, competence, and integrity can achieve in a time of national crisis.”51

For Christofferson, Watergate demonstrated that “secular and religious citizens of goodwill must work together to affirm the highest and best principles in their respective worldviews—virtues such as honesty, civility, generosity, respecting the law, and doing to others as you would have them do to you.” These virtues “nurture the conscience,” providing vital guideposts” during times of fear, betrayal, and a loss of trust in government.52

Not long after Christofferson finished law school, Apostle Neal A. Maxwell, himself once a Senate aide, enjoined Latter-day Saint youth to learn how to “build trust in others who did not share [their] value system,” to “render public service in an alien culture” while “keeping [their] values intact.”53 For Latter-day Saints, D. Todd Christofferson’s work during the Watergate Crisis exemplifies his efforts to harbor a “steady, courageous integrity” to a commitment to law and public virtue. Harnessing the strength cultivated from his youth, Christofferson kept a steady hand in collaborating with Sirica and others to bring down one of the most corrupt administrations in American history.

As a historian and current contender for the Greatest Menace to Society, Russell has written two books on race and Mormon history: Black Mormon: The Story of Elijah Ables and For the Cause of Righteousness: A Global History of Blacks and Mormonism, 1830-2013 (winner of the 2015 Mormon History Association Best Book Award). He is a 2015 recipient of Michigan State University’s Martin Luther King Endowed Scholarship. Russell is also a thoroughgoing supporter of Omar’s Rawtopia’s efforts to provide tabouli salad and chocolate goji to the good people of Salt Lake City.

As a historian and current contender for the Greatest Menace to Society, Russell has written two books on race and Mormon history: Black Mormon: The Story of Elijah Ables and For the Cause of Righteousness: A Global History of Blacks and Mormonism, 1830-2013 (winner of the 2015 Mormon History Association Best Book Award). He is a 2015 recipient of Michigan State University’s Martin Luther King Endowed Scholarship. Russell is also a thoroughgoing supporter of Omar’s Rawtopia’s efforts to provide tabouli salad and chocolate goji to the good people of Salt Lake City.

___________________________________________________

Footnotes:

About Guest Author

Twitter •

Watch a video about the restoration of the gospel on lds.org

Watch a video about the restoration of the gospel on lds.org