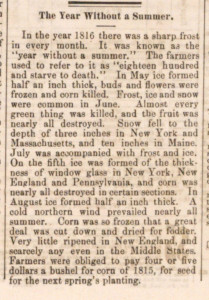

There are many phenomena which seem to defy reasonable explanation. Such is the case, for example, of the year 1816 which is known in history as the “Year without a summer” because of severe climate abnormalities that caused average global temperatures to decrease by 0.4–0.7 °C (0.7–1.3 °F). History also refers to that year as the “Poverty Year,” “the summer that never was,” “Year There Was No Summer,” and “Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death.”

The Cause and Effects of the Strange Phenomenon

The chain of events that developed into what would become known as “Year without a summer” were a result of a series of volcanic eruptions. Crop harvests in the areas of New England, Atlantic Canada, and parts of Western Europe had been poor for several years. The final devastating blow came in 1815 with the eruption of Mount Tambora located in Sumbawa, Indonesia.

History records that on 10 April 1815, Mount Tambora produced the largest eruption known on the planet during the past 500 years, erupting about 50-150 cubic kilometers of magma and measuring 7 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) scale. The eruption produced global climatic effects and killed more than 120,000 people, directly and indirectly.

According to an article in The Economist magazine dated 11 April 2015 titled “After Tambora”:

On the 10th and 11th [of April 1815] it sent molten rock more than 40 kilometres into the sky in the most powerful eruption of the past 500 years. The umbrella of ash spread out over a million square kilometres; in its shadow day was as night. Billions of tonnes of dust, gas, rock and ash scoured the mountain’s flanks in pyroclastic flows, hitting the surrounding sea hard enough to set off deadly tsunamis; the wave that hit eastern Java, 500km away, two hours later was still two metres high when it did so. The dying mountain’s roar was heard 2,000km away. Ships saw floating islands of pumice in the surrounding seas for years.

The year after the eruption clothes froze to washing lines in the New England summer and glaciers surged down Alpine valleys at an alarming rate. Countless thousands starved in China’s Yunnan province and typhus spread across Europe. Grain was in such short supply in Britain that the Corn Laws were suspended and a poetic coterie succumbing to cabin fever on the shores of Lake Geneva dreamed up nightmares that would haunt the imagination for centuries to come.

Mixed in with the 30 cubic kilometres or more of rock spewed out from Tambora’s crater were more than 50m tonnes of sulphur dioxide, a large fraction of which rose up with the ash cloud into the stratosphere. While most of the ash fell back quite quickly, the sulphur dioxide stayed up and spread both around the equator and towards the poles. Over the following months it oxidised to form sulphate ions, which developed into tiny particles that reflected away some of the light coming from the sun. Because less sunlight was reaching the surface, the Earth began to cool down.

At that time, Europe was still recovering from the Napoleonic Wars and suffered from massive food shortages. There were food riots in the United Kingdom and France, and grain warehouses were looted. Conditions in Switzerland, which had become landlocked, were worse as the famine caused such violence that the government had to declare a national emergency. In addition to those catastrophic events, huge storms and abnormal rainfall caused major European rivers to flood, including the Rhine River. Rainfall over the planet as a whole was down by between 3.6% and 4% in 1816. Between 1816 and 1819, a major typhus epidemic occurred in Ireland induced by the famine caused by the “Year without a summer” claiming the lives of approximately 100,000 Irish. An approximate European fatality total for the year 1816 was 200,000 deaths.

The crop failure in New England at that time is also attributed to the eruption of Mount Tambora. Prior to the eruption, the corn crop was flourishing. By the summer of 1816, it was reported that the corn crop had ripened so poorly that only about a quarter of it was useable as a food source. As a result of the crop failures in New England, Canada, and parts of Europe, the price of wheat, grains, meat, vegetables, butter, milk, and flour rose significantly.

It is further reported that the eruption of Tambora also caused Hungary to experience brown snow. Italy’s northern and north-central region experienced something similar, with red snow falling throughout the year. The cause of this is believed to have been volcanic ash in the atmosphere.

The Devastating Effects of the Phenomenon in North America

This strange turn of events which historian John D. Post has called “the last great subsistence crisis in the Western world” resulted in an agricultural disaster with major food shortages across the Northern Hemisphere. As aforementioned, most of New England, Atlantic Canada, and parts of Western Europe were the areas most affected.

This strange turn of events which historian John D. Post has called “the last great subsistence crisis in the Western world” resulted in an agricultural disaster with major food shortages across the Northern Hemisphere. As aforementioned, most of New England, Atlantic Canada, and parts of Western Europe were the areas most affected.

It is recorded that in May 1816 frost killed off most crops in the higher elevations of New England and New York, and on 6 June 1816, snow fell in Albany, New York, and Dennysville, Maine. In July and August, lake and river ice was observed as far south as northwestern Pennsylvania. A Massachusetts historian summed up the disaster:

Severe frosts occurred every month; June 7th and 8th snow fell, and it was so cold that crops were cut down, even freezing the roots …. In the early Autumn when corn was in the milk it was so thoroughly frozen that it never ripened and was scarcely worth harvesting. Breadstuffs were scarce and prices high and the poorer class of people were often in straits for want of food. It must be remembered that the granaries of the great west had not then been opened to us by railroad communication, and people were obliged to rely upon their own resources or upon others in their immediate locality (William G. Atkins, “History of Hawley” (West Cummington, Massachusetts (1887)), 86.)

For those accustomed to long winters, the weather itself was not as much a hardship as the effect that it had on crops, and thus on the food and firewood supply. During this period the prices for corn and grain rose significantly. The price of oats, for example, rose from 12¢ a bushel in 1815 (equal to $1.55 at today’s prices) to 92¢ a bushel in 1816 (equal to $12.78 at today’s prices).

The Joseph Smith Sr. Family – Joseph’s Leg Operation

Joseph Smith, Jr. was born on 23 December 1805, in Sharon, Vermont. He was the son of Joseph and Lucy Mack Smith. Shortly after Joseph’s brother, William, was born in 1811, the Smiths moved to the small community of West Lebanon, New Hampshire. Before long, typhoid fever came into West Lebanon and “raged tremendously.” The epidemic which affected the Smith children one by one, swept the upper Connecticut valley, leaving six thousand people dead.

Joseph Smith, Jr was seven years old at that time. After two weeks he recovered from his fever, but suffered major complications which eventually required four surgeries. The most serious complication involved a swelling and infection in the tibia of his left leg, a condition that today would be called osteomyelitis, leaving Joseph in agony for over two weeks. In her history, his mother recorded the love and tenderness that Joseph’s older brother, Hyrum, showed towards him during that two week period:

Joseph Smith, Jr was seven years old at that time. After two weeks he recovered from his fever, but suffered major complications which eventually required four surgeries. The most serious complication involved a swelling and infection in the tibia of his left leg, a condition that today would be called osteomyelitis, leaving Joseph in agony for over two weeks. In her history, his mother recorded the love and tenderness that Joseph’s older brother, Hyrum, showed towards him during that two week period:

Hyrum sat beside him, almost day and night for some considerable length of time, holding the affected part of his leg in his hands and pressing it between them, so that his afflicted brother might be enabled to endure the pain (Smith, History of Joseph Smith, p. 55.)

When the first two attempts to reduce the swelling and drain the infection in Joseph’s leg failed, the chief surgeon recommended amputation, but Lucy refused and urged the doctors, “You will not, you must not, take off his leg, until you try once more” (Smith, History of Joseph Smith, p. 56.)

The student manual for “Church History in the Fullness of Times” in chapter two of that manual titled “Joseph Smith’s New England Heritage” gives the following account of the operation on Joseph’s leg:

Providentially, “the only physician in the United States who aggressively and successfully operated for osteomyelitis” in that era was Dr. Nathan Smith, a brilliant physician at Dartmouth Medical College in Hanover, New Hampshire. He was the principal surgeon, or at least the chief adviser, in Joseph’s case. In his treatment of the disease, Dr. Smith was generations ahead of his time.

Joseph insisted on enduring the operation without being bound or drinking brandy wine to dull his senses. He asked his mother to leave the room so she would not have to see him suffer. She consented, but when the physicians broke off part of the bone with forceps and Joseph screamed, she rushed back into the room. “Oh, mother, go back, go back,” Joseph cried out. She did, but returned a second time only to be removed again. After the ordeal Joseph went with his Uncle Jesse Smith to the seaport town of Salem, Massachusetts, hoping that the sea breezes would help his recovery. Due to the severity of the operation, his recovery was slow. He walked with crutches for three years and sometimes limped slightly thereafter, but he returned to health and led a robust life.

The Joseph Smith Sr. Family – Norwich, Vermont

The family moved to Norwich, Vermont, about 1813. Joseph’s brother, Don Carlos, the ninth child in the Smith family, was born on 15 March 1816.

Most LDS writers accept the date of 1816 as the time the Smith family arrived in Palmyra, New York. Respectively, they place the duration of the Smiths’ stay in Norwich, Vermont (the town from which they departed for Palmyra) during the years 1814, 1815, and 1816.

This is based on Lucy Mack Smith’s historical account. In that history she recounts the family’s move to Norwich, Vermont, where they lived on a farm belonging to Esquire Murdock. She stated that the crops failed the first year, yet they were able to sustain themselves by selling fruit from the farm. The crops also failed the second year, but Joseph Smith, Sr. was determined to plant crop for a third year vowing that if he had no greater success than the previous two years, he would move to the state of New York, where wheat was raised in abundance. The third year the crops were destroyed by an untimely frost and he made preparations to go to New York. He left Norwich, Vermont, for New York with a Mr. Howard after making sure that his affairs were in order, leaving his family behind to pack and to get ready to vacate (Lucy Mack Smith, History of Joseph Smith by His Mother (R. Vernon Ingleton, 2005), 99-100).

This is based on Lucy Mack Smith’s historical account. In that history she recounts the family’s move to Norwich, Vermont, where they lived on a farm belonging to Esquire Murdock. She stated that the crops failed the first year, yet they were able to sustain themselves by selling fruit from the farm. The crops also failed the second year, but Joseph Smith, Sr. was determined to plant crop for a third year vowing that if he had no greater success than the previous two years, he would move to the state of New York, where wheat was raised in abundance. The third year the crops were destroyed by an untimely frost and he made preparations to go to New York. He left Norwich, Vermont, for New York with a Mr. Howard after making sure that his affairs were in order, leaving his family behind to pack and to get ready to vacate (Lucy Mack Smith, History of Joseph Smith by His Mother (R. Vernon Ingleton, 2005), 99-100).

According to Craig N. Ray’s FAIR article titled “Joseph Smith’s History Confirmed”:

With careful investigation of the extant Vermont and New Hampshire documents, these dates can be verified. The Smiths were in Lebanon, New Hampshire in May 1814, as the township tax rolls verify. Of equal importance, the Norwich town records report that Joseph Smith and his family were “warned out of town” in March 1816. This record, the only one found for a “Joseph Smith and family” found in the town’s “Warning Out” book, shows that the town’s selectmen issued the warrant on March 15, and it was served on the family on March 27, 1816. A “warning out of town” should not be thought of as a prejudicial treatment of the Smiths, because almost every family settling in a Vermont town in those days received such a warning. These warnings reminded strangers “that it was time for them to ‘depart this town. These “Warning Outs” consisted of two parts. The first part was the notification of the selectmen when strangers had been taken in. (This included information of arrival date and the previous town from which they could be sent back to.) The second part consisting of the warning out (meaning it was time to “depart said town hereof.”

As Ray points out in his article, a “warning out of town” by no means rendered any type of prejudicial treatment of the Smith family. “Warning out of town” was a widespread method in the United States for established New England communities to pressure or coerce “outsiders” to settle elsewhere. As Ray also points out, almost every family settling in Vermont at that time received such a notification. It is also interesting to note that the law was changed to disallow “warning out” in 1817.

Ray’s FAIR article also points out:

Rev. Wesley Walters found the second part of the notification, the warning out of town for 1816, for the Smith family. It is a paper on which the selectmen ordered the constable “to summon Joseph Smith and family now residing in Norwich to depart said town hereof.” This was dated “15th day of March AD 1816.” It was served on the Smith home on March 27, 1816.

The fact that three crop failures in a row caused the Smiths to be in a poor and destitute situation was probably a key in the selectmen deciding it was time to require the Smiths to “depart their town.”

The weather pattern for 1816 also helps to substantiate the final crop failure of 1816 that forced the Smith family to leave Vermont and move to Palmyra, New York. It was reported that the month of February was warmer than usual and crops were planted. However, by March, the weather took a turn for the worse, and “the people were visited by a piercing northeast wind, with a hail or drizzling sleet during the day. By the next day “the bloom of apricot and peach trees [were] covered with icicles” (C. Edward Skeen, “The Year without a summer: A Historical View,” Journal of the Early Republic (Spring 1981)).

The Joseph Smith Sr. Family – The Journey to Palmyra, New York

In his own history, the Prophet Joseph Smith does not state any reasons such as crop failure or unreasonable weather, for the family’s move to Palmyra. He only states, “My father, Joseph Smith, Sen., left the State of Vermont, and moved to Palmyra, Ontario (now Wayne) county, in the State of New York, when I was in my tenth year, or thereabouts” (Joseph Smith History 1:3).

The time came when Joseph Sr. sent for his family to join him in Palmyra. By the time that Lucy and the rest of the family had things sold and the rest of their debts settled, she only had $60 to $80 dollars left for the journey from Vermont to Palmyra. It was a 300 mile trip and the family faced many challenges along the way, such as the team master threatening to take the family wagon and team and throw the family belongings onto the street when Lucy ran out of money. Joseph Jr. who had surgery on his leg in 1812-1813, limped in the snow for most of the journey. It should be noted that the journey took place in the summer, thus the snow was an unusual occurrence. The journey itself lasted three to four weeks before the family was finally happily reunited in Palmyra.

About Keith L. Brown

Keith L. Brown is a convert to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, having been born and raised Baptist. He was studying to be a Baptist minister at the time of his conversion to the LDS faith. He was baptized on 10 March 1998 in Reykjavik, Iceland while serving on active duty in the United States Navy in Keflavic, Iceland. He currently serves as the First Assistant to the High Priest Group for the Annapolis, Maryland Ward. He is a 30-year honorably retired United States Navy Veteran.

Watch a video about the restoration of the gospel on lds.org

Watch a video about the restoration of the gospel on lds.org

Thank you this was most informative.